Each of us has a tendency to revisit certain intimate places in our lives: a street where we first met someone, a book by our bedside, a bench in the park. These semi-physical spaces are often viewed as personal and intimate, yet we share them with others, strangers and friends from current or bygone eras. They are historical places. Consequently, excavating the archaeology of one's own history is no lesser historical achievement than the discovery of Pompeii.

With Eye Dust: An Adaptation of a Novel to Come, Goda Palekaitė invites you to embrace this intimate approach to history. It's not based on unjust patriarchal facts, but on human intimacy and narrative.

Palekaitė is a Lithuanian artist who settled in Brussels after completing a postgraduate program at a.pass, a platform for artistic research and performance. Her work emerges from a disrupted temporality, where she welcomes figures from different eras. Through the fusion of fact and fiction, image and text, these characters spring to life in film, installation, scenography, or performance. Palekaitė transformed the exhibition space at Beursschouwburg into a bedroom where dreams and reality meld together. On a quintessentially gray, rainy day in Brussels, we met her, akin to a rolling amphisbaena, for a conversation about history, authorship, monsters, and human fictions.

Goda Palekaitė: The exhibition at Beursschouwburg is titled 'Eye Dust: An Adaptation For A Novel To Come'. 'Eye Dust' is a poetic combination of two words: 'eye crust' and 'sleep dust'. It refers to the only material remnant of that other world we inhabit during sleep. It's this notion of drowsiness that lingers upon awakening, which I wanted to use as a starting point. On the other hand, this exhibition is also an exploration of my narrative practice. The subtitle 'an adaptation for a novel to come' speaks to that. What the exhibition presents is essentially a precursor to what is yet to be written. I aimed to reevaluate the space of an exhibition and the space of a text, drawing inspiration from their atmospheres.

Charlotte Boddaert & Wolfram Vandenbergen: It does indeed appear as though you aimed to establish the material conditions in which a novel could come into being. To what extent is your work a search for material or inspiration for a novel?

GP: The idea to write a novel came before the invitation to create an exhibition. I wanted to write a novel in which various characters I was researching could meet each other. I wanted to see how their fragmented histories, which seem to have nothing in common from an external perspective, are still connected. When I say I research, I don't mean objectivity. Research, for me, is closer to discovery and forms of knowledge that arise from the liminal, the intuitive, the desiring. The characters meet through me, I invite them. It's almost like a birthday dinner, where friends can get to know each other. The bedroom seemed to me to be a suitable space for this. It implies an aspect of intimacy with the characters, these distant figures with whom I can never be physically intimate. The novel and the exhibition weave an intimate web together.

CD & WV: There appears to be a constant tension between the notion of history as a series of factual events and the subjective experiences that constitute this history. In your work, this boundary blurs as you interweave the fictional with the personal. What does history mean to you?

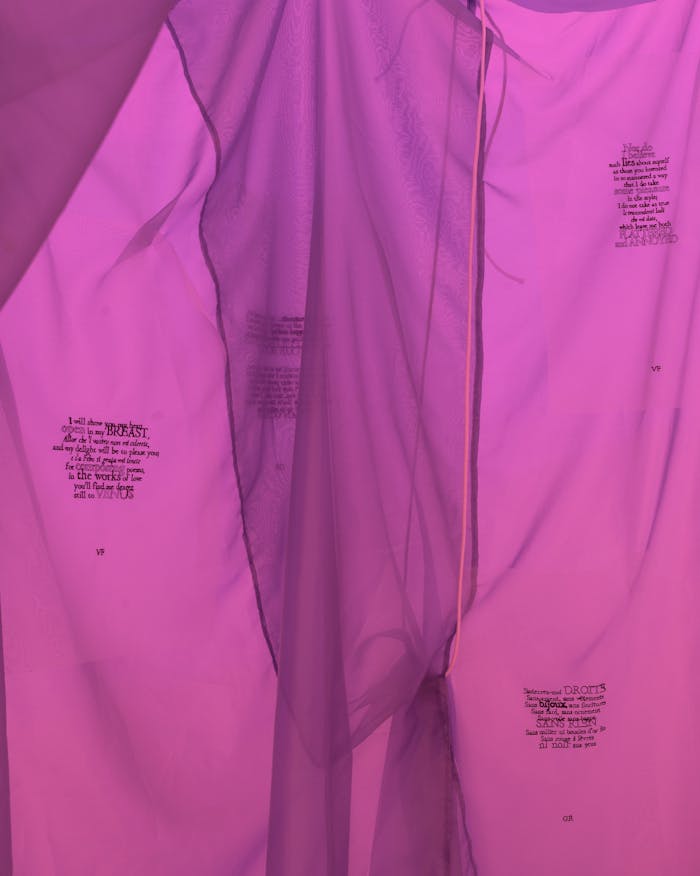

GP: It's no secret that the established academic history has been written as a white, patriarchal, and western system of knowledge. The active deconstruction of this discourse has been underway since the mid-20th century. This is important work that other artists and thinkers are engaged in. However, I've always found it more hopeful to not only think in terms of deconstruction, but also to generate new propositions. In an artistic context, I feel the freedom, the potential, and the privilege to engage with history in an alternative way, to employ a different language than an academic one. I partly see it as my responsibility to propose a different approach, which has become more clearly articulated in my work over the years. History is much closer to literature than it is to the sciences. The way historians assemble artefacts, facts, and other discoveries into a coherent whole, despite these findings being entirely fragmentary and not fitting together naturally, relies on the literary capacity of the historian. Often, the material is not complete, but that's not necessary either. The gaps are overlooked in historical accounts, but those holes and fissures in the material provide a fertile ground for creation. It's actually intriguing to keep the fragmentation visible and workable. Take the work of Sappho, for instance, which has never been uncovered in its entirety. Anne Carson's translation plays precisely with this, leaving the space between the poems printed in her edition If Not, Winter. It's this handling of remnants that informs my approach as well. In addition to a skepticism towards historical facts, I have a profound fascination for the outliers and leftovers from history. I focus on the historical elements that aren't taken seriously by academic circles, even though they hold importance. I'm interested in elements that only appear in the margins: visions, dreams, rumours, fictions, and rituals of unnoticed figures. For 'Eye Dust,' I created a canopy bed embroidered with texts by Grisélidis Réal and Veronica Franco. Franco was a poet and courtesan from 16th-century Venice, while Réal was an activist for the rights of sex workers in the 1970s. You read only a few passages from their poetry, in snippets of text that play with typography and translation. This way, I interlace their struggles and phrases, yet also preserve the fragmentation.

CB & WV: In your work, you also strive to consider the spectators and how they can be engaged in the work. The audience is assigned a more active and sensitive role through the body.

GP: Indeed, I do focus on creating a more affective experience for the spectator. The physical aspect plays a crucial role in my research and practice. I also seek intimacy through the personal, drawing from my own intimate context in the creation of my work. For the opening of the exhibition, I collaborated with both of my brothers. Jonas' (Palekas) practice stems from his background as a chef. He curated three different beverages, each embodying a bodily fluid for one of the characters in 'Eye Dust': The Sleeping Princess, inspired by the Khazar princess Ateh. The audience could choose a drink, a choice that revealed something about their future. This contributed to the physical experience of the spectators, who ingested this strangely flavored future. Adomas (Palekas) created the soundscape for the exhibition. He also composed the sound for two films featured in 'Eye Dust'. This results in the sounds of the film and those of the exhibition sometimes blending together. I strongly believe in this personal approach. I often collaborate with family, loved ones, people who are part of my personal life. This creates a more genuine and intimate atmosphere, a way to break down the barrier with the spectator in the exhibition space. The performative nature of my texts also contributes to this. Much of my writing initially takes form as scripts for film and performance. Through its dramatic aspect, the audience is brought closer to the historical characters, allowing them to come to life through their voice or the way they speak. This creates an intimacy between a visitor and the exhibition. They are invited to lie on the bed and watch films, to engage in an activity we do every day, but within the context of an exhibition. It's a way to test if we can even feel comfortable within that public setting.

CB: In I Write While Disappearing (2021), it seems that you aim to explore specifically female authorship by juxtaposing television footage of women discussing their authorship with your own reflections.

GP: The work indeed engages with the concept that Hélène Cixous referred to as 'l'écriture féminine'. However, my interest didn't primarily lie in female writing, which nowadays, I think, is somewhat of an outdated concept. I was more intrigued by the conditions that enable one to become a writer. When I looked at the authors from my personal history, I noticed that there were very few women among them. Therefore, I found it important to examine what women had to say about writing and what they had in common. What were the work and life conditions for female authors in the 20th century to be able to become writers? What allowed them to create those alternate worlds? What was their real, day-to-day experience like? On the one hand, the work revolves around both an expression of the political and social conditions of authorship. On the other hand, it also questions the relationship between oneself and their own discourse. Starting from the notion that what one writes has already been written, I sought to find what I could express through their words. It's a kind of writing that challenges the authenticity of one's words. Instead, it invokes my intellectual origin. The authors I read or learned about in school were presented to me within the context of the Lithuanian culture of that time. For instance, feminist theory did not exist in Lithuania in the 90s and early 2000s. It was something I only discovered when I was 25 and studying anthropology in Vienna. So, I had to reeducate myself. Therefore, I see the women in this film primarily as my teachers in literature and authorship. None of my past teachers were more important to me than them.

WV: Sofia Dati, who curated the exhibition, told us about the presence of the abject or monstrous in your work. It sneaks into the exhibition through the only non-human element in the space, your film Anthropomorphic Trouble (2021), which you created in collaboration with Adrijana Gvozdenović. From there, this monstrous quality is also evident in other works.

GP: Indeed, I would even dare to call it horror. Adrijana and I referred to Anthropomorphic Trouble as 'the animal horror movie', a film in which only animals would have a voice. The film was part of a project with the same title, addressing ecological challenges and our problematic relationship with the history of the Earth. The human representation of the world has never been seamless. There has always been an atmosphere of threat, danger, and doubt present in various world histories. An inspiration for the film was John Berger's "Why Look at Animals," which shows that as humans, we have always been able to hunt, domesticate, or ritualize animals, but truly understanding them has eluded us. The horror is the fear of that lack of understanding, of the unknown. We fear the future and the other, but that fear, that horror, remains a human construct. The world itself does not fear its end, nor do species fear their own extinction; that is a very human perception. The fear of the unknown thus turns certain beings into monsters. This is also evident in Biographic Disobedience (2020), where I reworked the ecstatic and erotic visions of women like Hildegard von Bingen or Teresa of Ávila into a performance, interpreted by performer Caterina Mora. Women have long been demonized by patriarchal powers such as the Christian tradition. The concept of the threatening nature was spread through Christianity along with the idea of the unpredictable character or the demonic nature of the feminine. Your fascination with the borderland between history and fiction is quite intriguing. It's compelling to consider certain ideas or practices that were once regarded as unquestionable reality, now classified as fiction. The horror genres in literature and film serve as apt illustrations. Take Princess Ateh, for instance. I present her as a sleeping beauty, but she can just as easily embody the concept of the vampire. Vampires are currently dismissed as characters from a literary genre, yet there exists an inexhaustible reservoir of documentation in the form of police reports, legal cases, and testimonies attesting to the very real presence of vampires. In essence, I create spaces and scenarios for characters that transcend the boundary between what is deemed real or fictional. These figures navigate through human history as outliers of the tangible, thereby challenging our representations of reality.

Lees de Nederlandse versie van dit gesprek hier.