Next year, the Broodthaers Society and KB45 (Art in Belgium since 1945) will organise The Unauthorized/Unexamined Marcel Broodthaers, a series of exhibitions, publications and performances celebrating the centenary of Marcel Broodthaers (1924–1976). In anticipation of the event, Joe Scanlan reflects on the present and future of the Belgian artist’s legacy.

Thirty-five years ago, in the introductory notes to October magazine no. 42, German art historian Benjamin H.D. Buchloh made an ambivalent, almost tortured case in support of an artist’s work — an artist who, in Buchloh’s mind, was already teetering on the brink of obscurity. That artist was Marcel Broodthaers.

Broodthaers had moved to Düsseldorf in 1971 to work more closely on several museum exhibitions and, to a certain extent, escape Belgium. Having been a visual artist there for seven years and a successful one, so to speak, for two or three, Broodthaers may have decamped to Düsseldorf in part to be less recognised, less understood. Parisian art critic Otto Hahn said as much in a 1975 interview in + − 0. When the editor of the Brussels-based magazine, Stéphane Rona, asked Hahn why Broodthaers chose Düsseldorf over Paris, Hahn replied that Broodthaers would have found himself too welcome in Paris, going on to say that ‘perhaps Broodthaers is like other Belgians, both in Belgium and elsewhere, who need to be surrounded by a hostile environment that doesn’t understand them. That’s what brings out the best in them. Maybe Paris would have been too easy; he would have felt understood and he would not have worked. Sometimes you need people to disagree with you in order to get your message across. In Germany he had a language barrier. He couldn’t speak.’ 1

Nonetheless, Buchloh published Broodthaers several times in Interfunktionen and even republished his most significant contribution to the magazine as a separate, limited edition artist’s book, Racisme Végétal. Alas, Broodthaers died three years later, Buchloh departed for North America the following year and neither conceptual art nor Düsseldorf would ever be quite the same. Another decade would pass before Buchloh penned the following words:

Just over a decade after the death of the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers in January 1976, his work appears to be confronted with the alternatives of oblivion or academic exhumation. At the same time, it seems almost impossible to avoid the consecration implied in a commemorative project such as this one. But neither oblivion nor canonization, neither margin nor center, are appropriate to Broodthaers’ work. And while this project must assume responsibility for whatever consequences it might engender, elevation of Broodthaers to the status of master, and the personal cult that such status often generates, would be the least appropriate reception of his work. 2

Much of what Buchloh feared has come true but not for the reasons he surmised. For one, Buchloh’s fraught dialectics of oblivion or canonisation, margin or centre, obscurity or institutionalisation have pretty much collapsed in today’s obsequious, wholly understandable art world. On the heels of Hermann Daled’s extraordinary transfer of over 100 Broodthaers works to the Museum of Modern Art, New York — an acquisition cemented by MoMA’s dutiful but dull retrospective the following year — Marcel Broodthaers would seem to have come and gone. A layer of dust was already visible on the vitrines even before the retrospective had closed. On a recent visit to see MoMA’s latest permanent collection installation I was only able to find one Broodthaers work on view — in a gallery whose theme was ‘Into the Void’. Indeed, as I gazed at rows and rows of Broodthaers’ handwriting, the reflections of viewers, like ghosts, played across his furtive signature. In the words of the great New York Yankee Yogi Bera, for Marcel Broodthaers it’s oblivion all over again. Only now that oblivion exists in the climate-controlled vaults of the most powerful museum in the world.

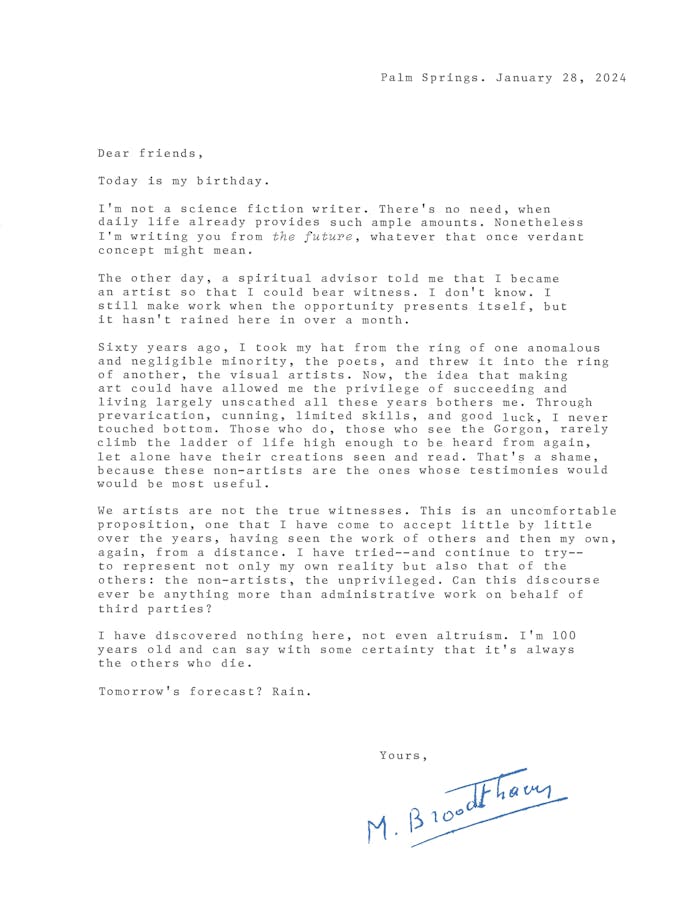

That’s not entirely bad. And it’s easy to imagine how Broodthaers might still have the last laugh. On the cusp of his 100th birthday, however, it seems more interesting to imagine what other kinds of oblivion might exist, for Broodthaers’ sake as well as our own. In my oblivion, Broodthaers is still alive: through a sleight-of-hand worthy of Monsieur de la Palice, Broodthaers faked his death (the fact that he died on his birthday has always dripped with lapalissadian suspicion) and escaped the art world altogether, landing in neither the Swiss alps, nor London, but California. It is there, in Palm Springs, that Broodthaers achieves a most satisfying oblivion: ignoring time, avoiding ambition, eschewing altruism, but chatting up the waiters, the Uber drivers, the concierge. In other words, inhabiting a state of utterly humane irresponsibility, just like all artists from the future do.

-

Otto Hahn and Stéphane Rona, ‘Marcel Broodthaers au CNAC a Paris’, in: + − 0, no. 11, Brussels, autumn 1975, p. 7–9.

-

Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, ‘Introductory Note’, in: October, no. 42, autumn 1987, p. 5–6.