From 27 to 31 March, the 23rd edition of the Courtisane Film Festival took place in Ghent. Pieter Van Bogaert visited the festival and paid particular attention to the echoes of one of the five thematic strands of the programme: Thinking with Dub Cinema.

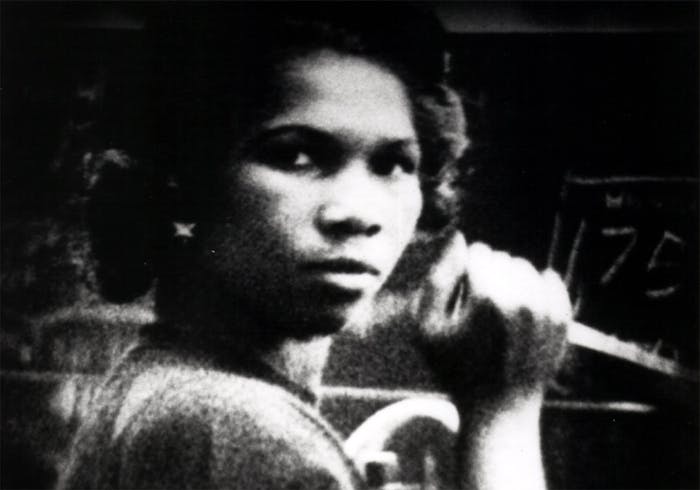

‘How many times can you watch Handsworth Songs?’ my cinephile friend asks. ‘I don't know,’ I answer, ‘ask Kodwo.’ Handsworth Songs, that's the film made in 1986 by the Black Audio Film Collective (BAFC) after the riots in the Birmingham neighborhood of the same name. The film is not really about the riots, but about what happened before, around and after those events – about the stories of the riots, and the stories around those stories. Kodwo, the name I give to my cinephile friend – that’s Kodwo Eshun, author of More Brilliant than the Sun, the cult book about black music from Sun Ra to Derrick May. We read and reread that book avidly during the final years of the last century. With Anjalika Sagar, Kodwo Eshun also forms the Otolith Group, a collective that makes films and in 2007 also produced an exhibition and a book about the BAFC, titled The Ghosts of Songs. My friend’s question comes after the Thinking with Dub Cinema study days during the Courtisane festival in Ghent in late March. Those study days began with Handsworth Songs, and Kodwo Eshun curated that part of the programme along with fellow filmmaker and researcher Louis Henderson.

My answer might as well have been: ask Courtisane. They’ve programmed Handsworth Songs on different occasions and in different contexts. There was the context of Figures of Dissent, an ongoing series of events exploring the politics of cinema that unfolded across different locations, starting with the 2015 edition of Courtisane. This time the context is Echoes of Dissent, a new research project by Courtisane collaborator Stoffel Debuysere on sound and cinema (and politics). I also remember an exhibition of the BAFC's work at Stuk in Leuven, curated by another Courtisane collaborator, Pieter-Paul Mortier. And I am sure I am forgetting some other times when the film was shown.

This much is clear: Handsworth Songs can be shown and viewed in many different ways. It is a historical document (from 1986). It begins with a historical event (in 1985). It frames that event not only in terms of racist motives, but also in terms of social, narrative or – this would not be a film festival otherwise – representational motives. A representation that is not only about image, but also about word and certainly about sound, where image meets text. That brings us to the idea of dub cinema, where stories (and the ghosts of the stories that precede and follow them), images (and the ghosts of the images that precede and follow them) and sounds (and the ghosts of sounds that precede and follow them) are layered through and over each other.

Dub cinema. Eshun first encountered the term in a 1988 article in The Village Voice by American writer and musician Greg Tate. In it, Tate writes of Handsworth Songs as dub cinema and of ‘dub (...) being the form of reggae where the lead vocal track is removed, and the foreground space filled with regenerated and decaying sounds bent on invoking a mythic African past and future.’ And further: ‘Handsworth Songs is a compressed chorus of black British voices, whose foregrounding puts white media and the police in the position of being Other.’ Eshun had already forgotten the term when he found it again years later in a text by Okwui Enwezor, the curator who brought Handsworth Songs to the (renewed) attention of Documenta 11 (the ‘documentary’ Documenta) in 2002. Enwezor writes: ‘The ghosts of these stories inform the notion of a historically infected dub cinema whose spatial, temporal and psychic dynamics relay the scattered trajectories of immigrant communities.’ Handsworth Songs is dub cinema, it is a mix tape that takes us back to Jamaica, to the plantation, to slavery. That historical context is not voiced but is present in the images. Dub is a process of distorting, of adding and of remixing in which space and time become confused. It is a process of endless repetitions, of versions, of reflecting an event and then reflecting the reflection. Dub works as an archive: of stories, of sounds, of images, of events. It is a way of organising, where misunderstanding is not a mistake but a crucial and deliberate effect.

Dub cinema is music that you can keep listening to, that you can cover again and again, and still always hear or see something different in it – always new versions. So, too, in Kodwo Eshun’s new reading of Handsworth Songs, which focuses on the camera shots in the film that show how the media reinforces and eventually takes over the role of the police. Eshun no longer sees the event through the television but instead looks at television as an event. He sees how the BAFC posits the whiteness of the media as structural, as institutionalised. Here, dub stands for making technologies of reproduction, revision and dissemination visible.

The experience of a festival like Courtisane is, of course, different for each visitor. Each visitor makes their own way through the many different lines and layers of the program. But for me, all these lines come back to dub. Dub as cacophony, as in Pickpocket, the 1997 film by Jia Zhangke. British filmmaker Morgan Quaintance wrote a text for Echoes of Dissent (the second in the series, after David Toop’s booklet on the work of Trinh T. Minh-ha) in which he emphasises the soundtrack of Pickpocket. He writes about Jia Zhangke’s quasi-documentary filming style, which incorporates shots of existing streets and markets and blends direct sound with another layer of other sounds. Quaintance calls it a dirty soundtrack, not only because of that layering, but also because of the quality of the sources: cassettes of Chinese pop music, karaoke and radio mixed with the ambient sounds recorded during the shooting of the film.

Cacophony was at it again in the Politics of the Voice programme, which featured live performances by several voice artists. Audrey Chen and Loré Lixenberg underlaid their own voices with the field recordings made in the city, an accompaniment of urban soundscapes. Lixenberg previously worked with a composition for Voice and City by Frederic Aquaviva, as well as with her own city recordings in Paris and London. She concluded her performance for Politics of the Voice with a Voice Party Anthem performed by the audience in the hall. Cacophony guaranteed. A very different experience of sound is offered by The Tuba Thieves, the festival’s opening film, made by visual artist and filmmaker Alison O’Daniel, who identifies as d/Deaf. The film is based on the true story of a series of tuba thefts in Southern California. It is a film about stolen sound, but also about tangible sound: the rhythmic bass notes of the tuba – the helpline that supports the rhythm of the band. To complete that experience, each viewer watches the film with an inflated balloon in their hands. These make the vibrations of sound tangible. A politics of sound (and unsound: sound and its absence) that not only makes sound palpable here, but also makes the silence audible in those moments when all you hear is the rustling of the balloons around you. It is a strange film about hearing differently. (And also about seeing differently: Why describe the sound and not the image? … is the absurd question that comes to my mind while watching the film.) A strange film in which the deaf main character prefers to settle behind a drum kit and Prince gives a concert for a deaf audience.

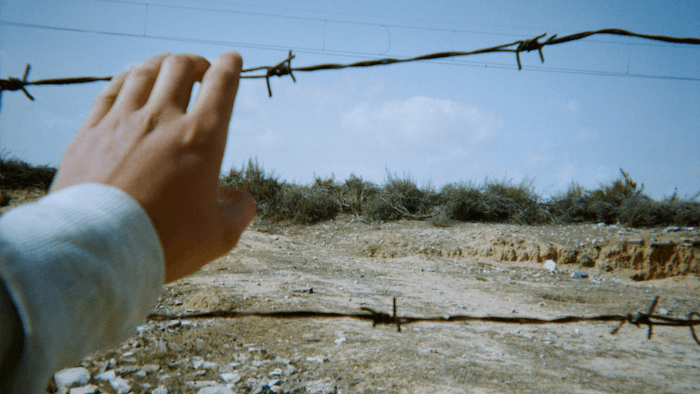

In terms of content, all of the works mentioned above make this edition above all a very open festival. A different experience for everyone. It depends on how you move through the different lines of the programme. This is a festival without end, a festival that is always beginning. That became clear again during the closing screening of Branden by Lisette Ma Neza Ntukabumwe and Bamssi by Mourad Ben Amor. The first film is a collective poem by Brussels’ first poet laureate about leaving, living and never arriving. The second is a long-distance collaboration centred on the images of a young Tunisian, edited by his Belgian cousin – a film about travel, risk-taking and dreams, symbolically presented here by the cousin, Fairuz Ghamman, and not the film’s Tunisian creator, who was denied a visa to attend the world premiere of his own work.