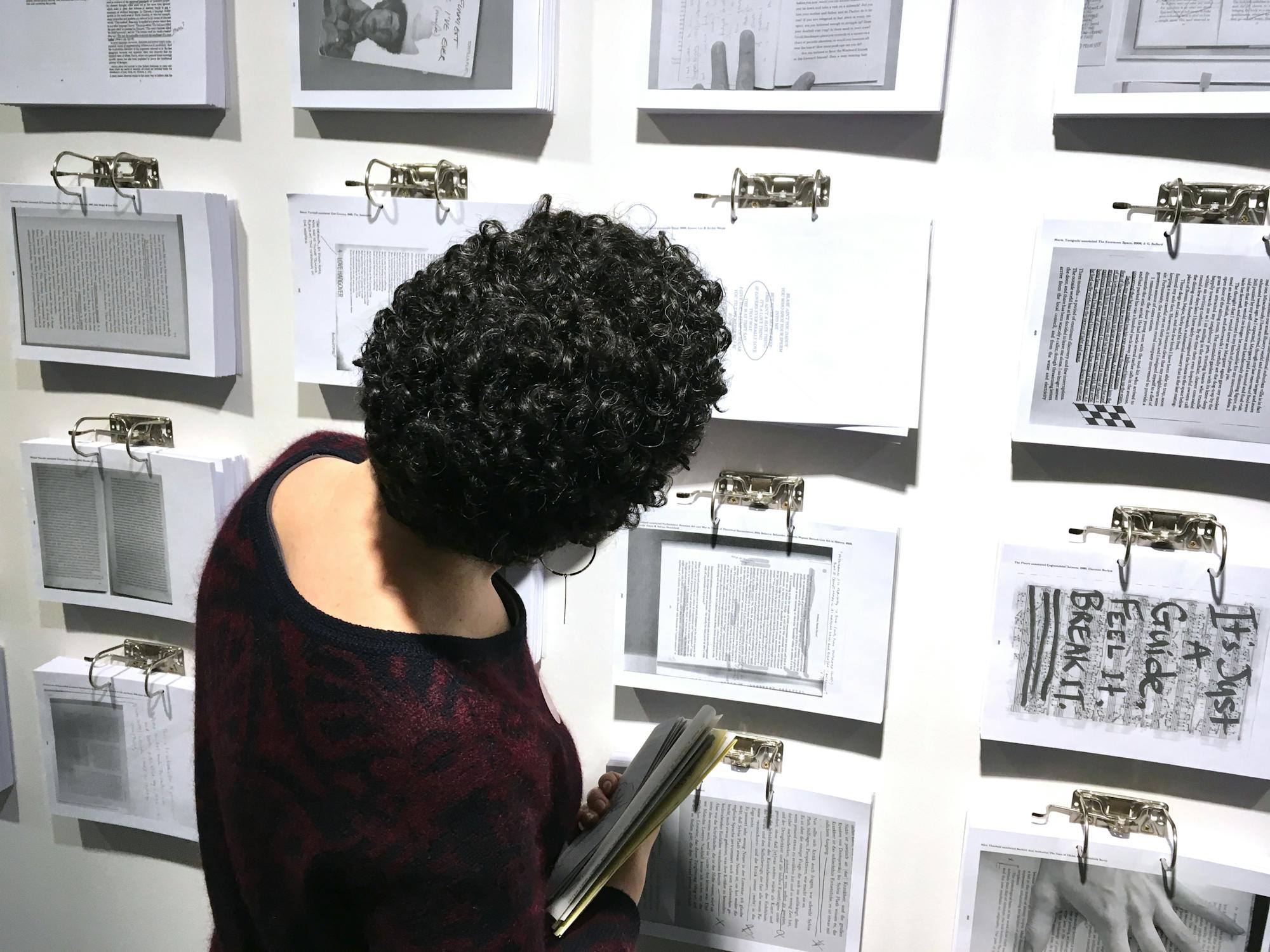

As part of a year-long programme on the upper floor of M HKA, artist-run organisation NICC (curator: Cel Crabeels) invited Ryan Gander to share his artistic practice with Antwerp, focusing on his preoccupation with education and annotations. The Annotated Reader (2018 —) is a project that acts as an exhibition-cum-publication in which Gander & critic Jonathan P. Watts invited hundreds of creative friends and personalities to contribute to a project that aimed to create a collection of their personally annotated texts; texts that have proven to be fundamental as a source of inspiration, essential for their careers or simply beneficial to their peace of mind. 281 contributions were collected and are now made public. The response brings together multiple writings with a variation of different notations from scribbles to sketches, collages to cartoons, underlining to completely deleting.

Pieter Vermeulen: When and how did the idea of The Annotated Reader come about?

Ryan Gander: “Every time I prepared a lesson or a studio visit with students, I always thought it'd be good to save the handout so I could give them to people afterwards. When I was giving people handouts I started to ask them what they thought would be a good handout. So art students were giving each other handouts of what they found inspirational. When you annotate a handout, you give your perspective on it. So from the handouts I got the idea of making a book, which would be a really good resource for anyone who’s teaching. Anybody could use it. In fact it didn’t start as a book, but as a lot of sheets of paper that were all stapled together. I thought I could give that to other people so they could just distribute it.”

PV: As a title, The Annotated Reader sounds slightly academic at first, but I noticed that reading it is actually a whole lot of fun. Do you think pleasure, or the pleasure of learning, is an essential component of the project?

RG: “I always think that the word research has a big stigma, people think it is boring. But just living is research in itself. I'm the type of person that if I get into a library, it feels like being in heaven. So it just depends on your perspective on it. Our greatest pleasure as humans is education. People tend to think learning is for young people but it’s a lifelong activity. And there's no greater pleasure.”

PV: How did you make the selection of contributors to the reader?

RG: “I don’t know everyone. I made the selection together with Jonathan P. Watts, the other editor. We tried to be as diverse as possible. Not from a social identity viewpoint – it’s not about equality as much. But when you pick someone who speaks Japanese you would get a Japanese text. And when you choose a musician, you might get a musical score. When you choose an actor, you might actually just get one line from a script. I wanted the book to be about the differences in opinion and the way that opinions collide and bang against each other like noises.”

PV: Do you see this project as a further extension of your already multifaceted practice? I remember you once said that among your many other activities, it's writing you like the most.

RG: “I think it has less to do with which activity I like the most, and more with the change and difference between each activity. I’ve written children's books, created television programmes, designed trainers for Adidas, made a chess set, been commissioned to create public art, amongst many other things. It's the space between them and the jump that I enjoy.”

PV: You’re more interested in the journey. The objects are like the “receipts”, you once said.

RG: “I think that’s an observation that could go for any piece of conceptual art, really. To understand an object or a thing as art, is really just a capitalist mentality about things, progress, gain and, essentially, more stuff. It’s more stuff that’s ruining the planet and compromising our future. So, for me, the artwork is the story, not the thing that represents or carries the story. The thing is the vessel.”

PV: Do you think it's important to build more bridges between presentation and education, between making and learning, between exhibitions and publications or even between the art world and academia? Because that's what the project seems to be doing.

RG: “Again, the space between things and diversity is what makes the world interesting. I think, essentially, any good artwork is about research and discovery, about learning and finding something out. You know, turning stones over and seeing what's underneath them and things like that. So yeah, I mean, if you're an artist and you make a project and you know the outcome already, I would question if that is actually art. Because, for me, art is about discovery.”

PV: The Annotated Reader is also related to a video you made in 2017, The Artist is Not for Turning - Relic Gestures.

RG: “That video is shown in the same exhibition at M HKA because that's where my obsession with annotations comes from. That’s where it started. The video work was originally made as part of Nuit Blanche in Paris, in October, 2016. We basically organized a performance with 200 amateur actors who like to dress up as zombies. We gathered these people in a huge sports hall and shot a scene where they were walking along the banks of the Seine.”

“For this particular video, I shot a video of a well-known British political BBC news TV presenter, Clive Myrie, reading a speech written in the 1970s by zoologist Desmond Morris called ‘Peoplewatching’. It looks like the BBC News is reading a sociological text but then behind him are hundreds of zombies walking past, which he completely ignores. This is shown with annotations of the text written on the video as well. The video is actually annotated but the text is deleted. It’s actually quite hard to explain. You basically get my annotations of the text over the top of the video.”